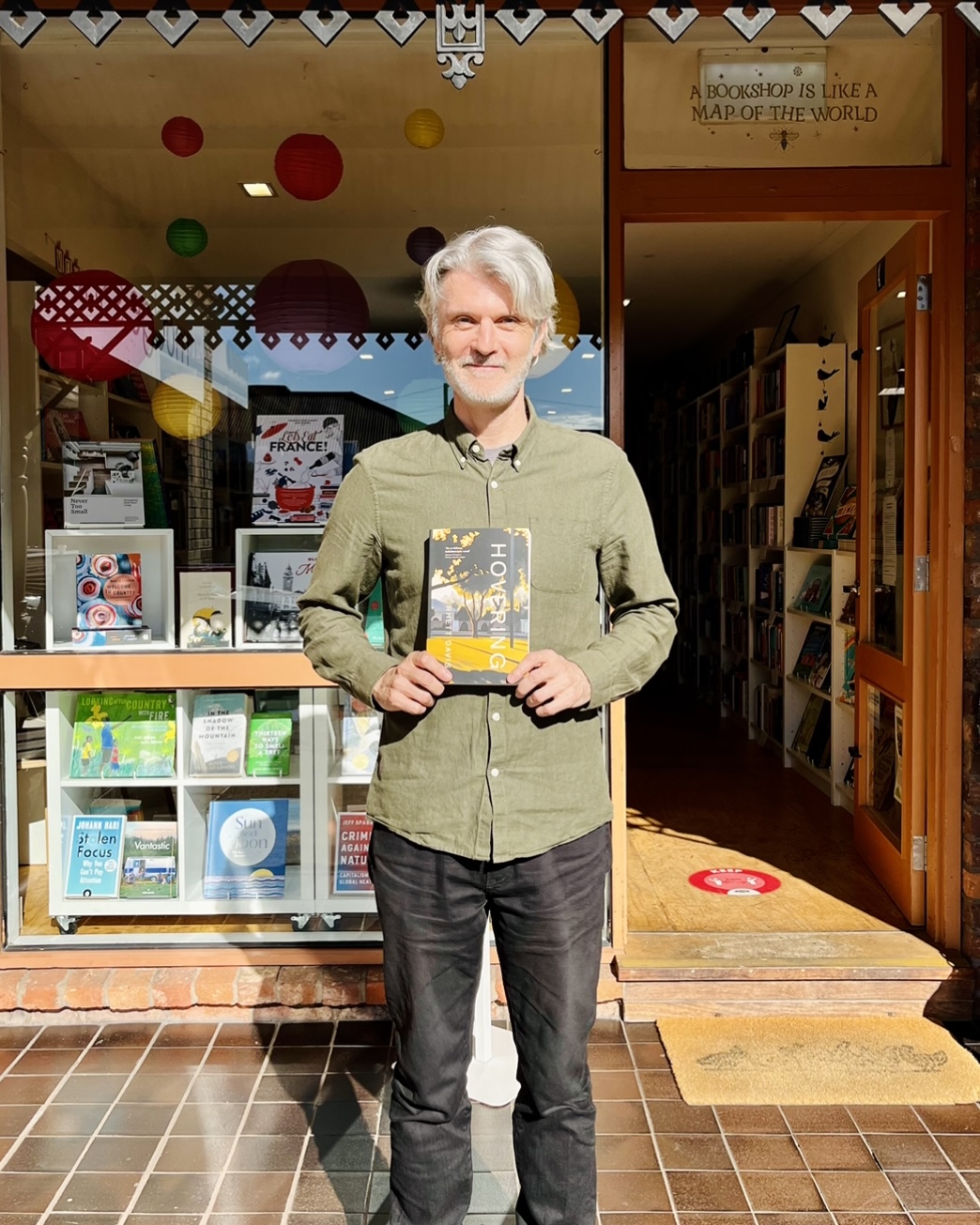

Well, this is a very exciting moment for us! We have been following Rhett Davis’ writing journey for some years now, from his PhD in Creative Writing at Deakin University, to winning the 2020 Victorian Premier’s Literary Award for an Unpublished Manuscript, through the editing and publishing phase, and now to the release of his debut novel Hovering. Rhett is also an ex-Book Bird, having worked at the shop for a stint during the writing of the manuscript. Hovering is a spectacular novel about a city in flux; a disturbed, restless city in which streets and buildings and other infrastructure suddenly change locations. It’s also about art and colonialism and digital culture, and woven together with many different forms of storytelling, like computer code, texts, and newspaper reports.

We’re excited to be bookselling at the launch at Geelong Library on Wednesday 2 March, where Rhett will be in conversation with another Book Bird favourite, Maria Takolandar. This is a free event, and you can register here. You can also pre-order a copy of Hovering on our online shop here. But for now, please enjoy our conversation with Rhett about the inner workings of his book, Hovering…

Your debut novel, Hovering, depicts a city that is constantly changing: its roads change direction overnight and houses that were once in one suburb suddenly find themselves in another. The city, Fraser, feels like it’s alive, and the residents of Fraser must try and deal with it as best they can. What made you want to write about a city in radical flux, as opposed to how we tend to think of cities and places, which is more fixed?

Firstly, thank you so much Book Birds! I’ve been coming to the shop since Anna opened, have browsed for far too long at times and have been recommended some truly wonderful books. It’s incredibly special to be able to see Hovering on the shelves.

The idea of writing about a city that transforms itself was seeded a few years ago. I used to work near Johnstone Park in Geelong. I was walking home one evening after a flash flood and the entire park had filled with water. It had become what it once was – a small lake – in the space of a half an hour. And it struck me that our attempts to build cities and structures that resist nature can’t hold forever. The earth moves, the water rises, the wind picks up a roof and throws it hundreds of metres away. And there was something in that idea, an absurd one of course, of a city that was itself agitated.

I like to think that absurd or surreal stories can shift our thinking a little from preconceived ideas. In this case, the idea that our cities are fixed and permanent, when they grow and shift and are anything but stable.

The protagonist, Alice, returns home to Fraser after sixteen years away and finds her home city both familiar and unfamiliar, which I think is a feeling many can relate to when they return to a place after a long absence. She returns not only to Fraser, but to her sister Lydia, and the two women could not be more different. Can you talk a bit about the opening premise of your book and the relationship between the sisters?

Alice comes home reluctantly and finds it hard to connect with what it was. It is a feeling I’m familiar with myself, having lived overseas for several years at various times and returning home to Geelong. There is always a strange period of time after returning where your memory has to catch up with what is there now. It could simply be a few new cafes, a completely new road, or a building that has disappeared. And for much of the novel Alice is struggling with this distanced, uncanny feeling of the unfamiliar familiar.

Lydia, on the other hand, has never left. Alice’s departure caused deep resentment that has festered, and the idea of her estranged sister turning up on her doorstep after all these years of silence fills her with dread. It’s not a conflict they’ll easily resolve.

The tension between moving from home and staying is something I’ve personally felt for many years. I love my home but I often want to leave it. But then I want to come back again. It’s all very confusing. The different journeys that Alice and Lydia have gone on are two extreme versions of that, and I wanted to bring them together to see where they landed themselves!

One of the other main themes in Hovering is coding and digital culture. George, Lydia’s teenage son, and his mother are often plugged into virtual realities (games, for instance) that are more lush, more natural, than the world outside, in suburbia. What role does virtual experience play in your novel?

I wanted the novel to explore the relationship between the digital world and the physical world, particularly in an age where formerly physical actions are increasingly occurring virtually (i.e. meetings, shopping, conversations, whatever Meta is going to be, etc.). We give so much of our lives now to the digital world, whether it be through games, social media, or other online content. It’s an alluring reflection of the physical world that can allow us to do some amazing things, but can also be unrealistic, addictive, divisive, and nonsensical.

In Hovering, Lydia is fully immersed in online games and endless streaming series’ in a way that’s not very healthy. George in contrast to Lydia has quite a healthy relationship with the digital world and uses it both to make an income and express himself creatively. The point I was trying to make isn’t that the digital reflection of the physical world is good or bad, but that it is often inseparable from the physical world, and is an ingrained part our lives and our stories.

Hovering is a postcolonial novel examining the enduring legacies and violence of colonisation. Can you talk a bit about this theme of the book, and how it informed your characterisation of Fraser?

I’ll go back to Johnstone Park again for a moment. Pre-colonisation, the park was a water source for the Wadawurrung. It was taken, dammed, and apparently became something of a cesspool. After this, it was drained and turned into a park. By this time, in the late 1800s I believe, the last of the Wadawurrung people who were still living traditionally had died. The history of this park feels to me like a micro-history of this country. And so in the flash flood I mentioned earlier I saw something else, something mournful, something about what was and what was lost and what could have been. The city of Fraser in Hovering is agitated. There are perhaps many reasons, and I’d mostly want to leave it to readers to determine what they are, but I will say that the city is infused with the unresolved debts of this country and its treatment of First Nations people.

You experiment with storytelling a lot in the text. Some chapters are written in HTML code, some as online chats, texts, and comments, and some in columns showing the simultaneous thoughts and actions of characters. How did you decide upon the best way to tell and present the story?

I do! It’s a lot of fun to write this way, and I hope fun to read as well. But there was a serious purpose. I wanted the novel to reflect the way we consume online media both in its prose and its form. I’ve always loved novels that approach fiction from unexpected angles. I took a few ideas – the fragments of social media commentary for example – and played around for a while. At one point I actually ‘translated’ sections of an online newspaper and some YouTube videos into plain text, just to see what it would look like.

I’m hopeful the storytelling fragments that came from this have been used sparingly enough to get the point across without getting in the way, and that they make the reading enjoyable. If anyone is struggling with them – as my father was at first – the main thing I would suggest is to look for the human in the noise.

And for the record, my favourite is the transcript of football commentary.

Who were some of your literary influences as you wrote the book? Particularly any writers who informed your ideas of unstable cities or alternative ways to present and play with narrative?

So many! But I’ll keep it short. Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino was pretty central. It’s a book I’ve loved for a long time. In some ways it just describes dozens of fantastic cities. But Calvino is also showing that our cities are completely different depending on which way we look at them. I wanted to write about a city with that sort of spirit, an evasive, capricious city that refused to be classified.

Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From The Goon Squad and George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo were both big influences. They combine formal play with beautiful, funny and resonant stories. BS Johnson’s Albert Angelo features a brilliant section of simultaneous narrative in which the narrator, a teacher, presents to the class in one column while coming close to a breakdown in the other. Like much of Johnson’s work it’s a little heavy, but it’s an incredible piece of writing that entranced me.

And here’s one that I just thought of: Shaun Tan’s The Arrival. It’s a sublimely weird graphic novel of a man arriving in a foreign city, and it left a huge mark on me that echoes in Hovering. But I could also say that about Suburbia and most of Shaun’s incredible, surreal work.